inside abravanel

The Story of Our Namesake

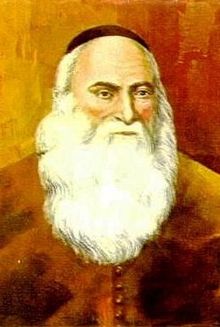

The Story of Don Isaac Abravanel

The following article was reproduced with permission from:

“The Story of Don Isaac Abarbanel.” Jewish Image Magazine (2006): 176-180.

n the annals of Jewish history, the name Don Yitzchak Abravanel has assumed legendary status. A towering figure renowned for the brilliance of his commentaries on the Torah, as well as for his supreme integrity and righteousness, his accomplishments in affairs of, state and finance were no less noteworthy. Moving easily between the worlds of Torah scholarship and statesmanship, Abarbanel shines as a paradigm of the melding of Torah erudition and financial and diplomatic genius.

Born in Lisbon in 1437 CE (AM 5197), Isaac Abravanel was descended from an illustrious Sephardic family, which traced its lineage all the way back to King David. The title ‘Don’ (Minister) was conferred on him when he served as minister of finance in the Spanish government. Thus, he is often referred to as Don Isaac Abravanel, a fitting appellation for a man who was a legendary advocate for his fellow Jews.

Isaac’s grandfather, Samuel Abravanel, a great Torah sage from the Spanish city of Seville, escaped from that city when its Catholics destroyed the Jewish quarter and butchered many of its Jews. Samuel’s home was well-fortified and he managed to escape and flee to Portugal.

Isaac’s father, Judah Abravanel, was a very successful merchant, and influential in the royal court. Recognizing Isaac’s unique capacities, Judah hired the finest teachers to study with him, among them Rabbi Joseph Chaim, Lisbon’s Rabbi and author of Mile! d’Avos. Later on, Isaac went to Holland to study under Rabbi Isaac Abutlav, author of Menoras HaMaor.

When Abravanel was only 20, he wrote his first book, Ateres Zekeinim, which discuses such subjects as prophecy and Divine Providence. At that time, he also began to compile his famous commentary on the Torah.

Aware of Abravanel’s intelligence and business acumen, Portugal’s king, Alfonso V, appointed him to the position of Royal Finance Minister. That involvement caused Abravanel much sorrow, because he preferred to devote himself to Torah study, and to completing his commentary on the Torah. However, he used the prestigious position as finance minister as a vehicle for helping his fellow Jews.

He possessed considerable wealth and his house, which he himself tells us was built with spacious halls, was the meeting-place of scholars, diplomats and men of science. Among his other occupations, he busied himself in ransoming Jewish slaves, obtaining the co-operation of some Italian Jews in this effort. When Arzila, in Morocco, was taken by the Moors, and the Jewish captives were sold as slaves, he contributed largely to the funds needed to redeem them, arranged for collection throughout Portugal on their behalf, and assumed personal responsibility for their housing and welfare.

Alfonso died in 1482 CE (AM 5242) and was replaced by his son, Johan. Johan was a very different man than his father, and he set about eliminating those whom he feared, including the Duke of Braganza who was executed on the charge of conspiracy. Johan accused Abravanel, who had good relations with the Duke, of conniving with him against the king, and Abravanel was summoned to appear before him. Abravanel, warned of the king’s subterfuge in time, saved himself by a hasty flight to Castile in 1483.

The king sent mounted soldiery after him, but they could not overtake him, and he reached the Spanish border in safety. In a letter to the king, he declared both his own innocence and also that of the Duke of Braganza. The suspicious tyrant gave no credence to Abravanel’s defense, and his large fortune was confiscated by royal decree, as was that of his son, Judah Leon, a physician.

Taking his family with him, he settled in Spain, which was under the rule of King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile. In his new home in Toledo, Abravanel at first occupied himself with Biblical studies, and in the course of six months produced an extensive commentary on Nevi’im Rishonim: Yehoshua, Shoftim and Shmuel.

Shortly afterward, he entered the service of the house of Castile. Together with his friend, the influential Don Abraham Senior of Segovia, he undertook to farm the revenues and to supply provisions for the royal army, contracts that he carried out to the entire satisfaction of Queen Isabella. However, this period of tranquility was not long lasting.

At that time, both Moslem and Christian provinces dotted the Iberian Peninsula where Spain is situated. Seeking to gain total sovereignty of the Iberian Peninsula and to unite all Spain under Catholic control, King Ferdinand waged war against the Moslems, motivated by his desire for power and wealth. His wife, Isabella, supported these campaigns, although in her case, she was motivated by religious fanaticism, spurred by the priest Torquemada, to whom she always made her confessions.

In 1487 CE (AM 5247), Ferdinand and Isabella captured the Moslem province of Malaga. Summoning Abravanel to the royal court, Ferdinand appointed him finance minister and asked him to come forth with the vast sums needed to wage a war against Granada. With Abravanel’s aid, Ferdinand gained control of Granada, too, and became the sole ruler of the Iberian Peninsula, as well as the undisputed monarch of a united Spain.

Now that Spain was rid of the Moslems, Torquemada prevailed upon Ferdinand and Isabella to banish the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula.

When they first learned of the threat of expulsion, Spain’s Jews did not really believe it would happen, since they had contributed vast sums to the war effort and were still needed in Spain. Abarbanel did not despair, and thought he could convince Ferdinand to reverse the decree. Although he warned Ferdinand that expulsion of the Jews from Spain would devastate the country financially, and that it was doubtful that Spain would ever be able to stand on its feet again, Torquemada’s arguments won the day, and in March 1492 CE (AM 5252), following the final triumph over the Moors after the fall of Granada, Spain’s Catholic monarchs issued the Alhambra Decree, ordering the expulsion of all Jews from Spain and its territories and possessions by July 31, 1492 (Tisha B’Av).

Ferdinand and Isabella offered Rav Yitzchak the opportunity to remain in Spain and to continue to officiate as its finance minister, without having to renounce his faith, but he spurned their `generosity’, and chose to join his people in their exile and wandering.

On Tisha B’Av of 1492 CE (AM 5252), 300,000 Spanish Jews left behind all of their wealth and prestige, and set out into the unknown. They were led by Abravanel, who was a source of solace to them on their treks. Within the terms fixed by the edict of expulsion, the Jews sold and disposed of their property for a fraction of its true value; fine houses and estates were sold for trifles; a house was exchanged for a mule, and a vineyard given for a little cloth or linen. The rich Jews paid the departure expenses of the poor, practicing toward each other the greatest charity so that, except for a very few of the poorest, they would not become converts.

The rabbis permitted the Jews to play music during the trek, despite the laws forbidding such merriment during the three weeks leading up to Tisha B’Av. They ruled that it was a mitzvah to raise the spirits and celebrate the bravery of Jews who were ready to give up everything and face a hostile world in hunger, disease and poverty in order to sanctify the name of God. In this way, they defied the vicious designs of Ferdinand and Isabella, and the fiendish Torquemada, who thought they had broken the Jewish spirit by expelling the Jews from a country where they had seemingly enjoyed a golden era of Torah, wealth and influence.

Don Isaac Abravanel encouraged the women and young people to play on pipes and tambourines to cheer the people, and thus they left Castille and arrived at the ports of the sea, from where they dispersed to many places.

Abravanel and his family found asylum in Naples, where he completed his commentary on Melachim. His talents were called upon by the king, whose service he entered. He remained in Naples for seven years. However, his wanderings were not yet over, for in 1495, the French invaded Naples. When the city was taken by the French, Abravanel followed the young King Ferdinand to Messina, abandoning all his possessions in the process. From there he moved on to Corfu. In 1496, he settled in Monopoli, and finally in 1503, he moved to Venice. As was the case wherever Abravanel settled, his brilliant reputation accompanied him. The Senate recognized Abravanel’s greatness and talents, and his services were employed in negotiating a commercial treaty between Portugal and the Venetian republic.

Abravanel remained in Venice for the rest of his life and finally completed his commentary on the Torah. The commentary on the Torah and Prophets are his major works.

Abravanel felt deeply the hopelessness and despair that possessed his fellow Jews in the years following their expulsion from Spain. Having personally witnessed the suffering of the exiled Jews, and fearing that their troubles might weaken their faith, he devoted parts of his writings to encouraging them to remain steadfast in their faith and to await the geulah, the coming of Moshiach.

Thus, he wrote a commentary on the Book of Daniel, Mayenei HaYeshu’ah (Sources of Salvation), Yeshuot Meshikho (The Salvation of His Annointed), and Mashmia Yeshuah (Proclaiming Salvation). In one place, he writes: “Fortunate is he who waits. Fortunate is he who bore the suffering of the exile with pride and accepted the suffering and trials with love, remaining staunch in his faith and in his anticipation of the imminent geulah.”

Other works include a commentary on Rambam’s Moreh Nevuchim, Nachlas Avos on the Haggadah, a commentary on Pirkeis Avot, and Rosh Amana, a dissertation in defense of the Rambam’s Thirteen Principles of Faith.

His commentaries on Tanach are unique. Before each chapter, he presents challenging and pointed questions for the student. He then answers the questions systematically, in light of the parsha or chapter to which they pertain.

In a letter written to Shaul HaCohen in 1507 CE (AM 5267), Abravanel laments the fact that he had to spend so much time in royal courts and palaces, instead of on his writings. However, he also says that his sole purpose in occupying such positions was to help the Jewish people.

Don Isaac Abravanel passed away in Venice in 5268/1508, and was buried in the old Jewish cemetery in Padua, beside Rabbi Judah Mintz, the Chief Rabbi of Padua who had passed away five years beforehand. News of the death of the great Torah sage and interceder for his people spread rapidly throughout the Diaspora, and Jews everywhere mourned the great loss.

Abravanel’s prodigious output of Torah commentary was the greatest of the enduring legacies he bequeathed to his people. In addition, he serves as a role model of the Jewish spokesman for his community, and interceder on its behalf. A statesman whose diplomatic career spanned three countries in turn of the century Europe, his vast political experience no doubt was reflected in his Torah commentaries, rendering the works of the scholar-statesman of Spain, in many senses, ahead of his time.

we achieved

through our charitable actions

We need your partnership

Freemasonry is the world’s first and largest fraternal organization, and is based on the belief that each man has a responsibility to help make the world a better place.

Through our culture of philanthropy, we make a profound difference for our brothers, our families, our communities and our future.

Contact us today for more details!